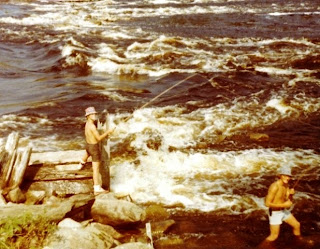

Residents of makeshift villages gather around a U.S. Air Force C-5 Galaxy transport in Goma, Zaire, during the summer of 1994 to unload water purification equipment. Photo by Keith Michaud

Resisdents of nearby makeshift villages gather to watch water purification equipment unloaded from a U.S. Air Force C-5 Galaxy transport bringing water purification equipment to refugee camps near Goma, Zaire. Photo by Keith Michaud

July 28, 1994

Clashing with cholera

Travis delivery helps refugees in Zaire

(Reporter staff writer Keith Michaud and photographer Joel Rosenbaum accompanied Travis (Air Force Base) crews on their mission of mercy to Africa. Look for more of their reports this weekend in The Reporter. – Editor)

By Keith Michaud

Staff Writer

A C-5A Galaxy transport plane from Travis Air Force base delivered much-needed water purification equipment to Zaire on Tuesday, helping Rwandan refugees battle a deadly outbreak of cholera.

By Wednesday, the equipment was working and delivering purified lake water to thousands of refugees in camps near the border town of Goma.

The relief effort, however, was hampered by a lack of trucks to deliver water. United Nations officials were able to round up only two leaking, half-busted tanker trucks.

U.N. organizers, overwhelmed by the crisis, said they were searching for tanker trucks in Zaire and shipping in about 10 tankers from Uganda and Croatia, but were able to rent only a few from gasoline shipping companies Wednesday.

The Travis transport, manned by reserves from the 349the Airlift Mobility Wing, traveled for nearly 24 hours with at least three mid-air refuelings to deliver the water purification equipment and the seven-man crew from Portable Water Supply Systems. The Redwood City company set up an above-ground water system to pump 100,200 gallons of lake water every minute to eight water purifiers.

Company owner Frank Blackburn said he and his crew will use two miles of hose to bring water from Lake Kibu, near Goma. Water there has been fouled by dead bodies and human excrement, worsening the cholera epidemic.

Blackburn, a former San Francisco Fire Department assistant chief with 34 years experience in firefighting and disaster planning, said his company helped provide water during the Loma Prieta earthquake and the Oakland Hills firestorm.

“This one is different because there’s a lot of people dying over here,” he said, aboard the C-5A.

Blackburn’s son, Matthew, is with the crew.

“For him, it’s a workshop,” Blackburn said of his son, a University of California, Davis, student studying international relations.

Hundreds of refugees, French airmen, and U.N. representatives greeted the transport when it landed at the now-busy airport in Goma. Children scattered from the runway as the huge jet touched down.

Not far away from where the plane was unloaded were two bodies and piles of rocks some said where graves. A member of the U.S. military assessment team said bodies also were outside the airport entrance, mostly because the airport is between the contaminated lake and a refugee camp.

“Every day, a thousand more dead,” said French Air Force Capt. Jacques Albert Roussel. “It is terrible. In front of the (airport) there are dead.”

Roussel and other French airmen have been in Zaire for a month. Roussel said the relief effort was a good thing.

“It’s difficult, but a beautiful mission because we do it for them,” said Roussel, pointing to the hundreds of refugees gathering to see the transport.

As the crew finished unloading equipment, a funeral procession moved from nearby huts, along the edge of the runway, behind palm trees. Children begged for money, business cards, to have their photograph taken, or anything American.

U.S. Army Maj. Guy Shields, part of the military assessment team at Goma, said the purification equipment delivered Tuesday is much needed. “Those are going to make a big dent.”

Shields said the local government and humanitarian groups were cooperating with the advance assessment team. He said one of the early problems was getting aircraft unloaded at the airport; at first planes were unloaded by hand.

“The biggest thing here was to ease up on the congestion at the air field,” said Shields. “And the next thing was to bring in water.”

U.S. Air Force Capt. David Burgess was helping deliver Red Cross supplies to Nairobi, Kenya, when he asked if someone was needed to assess the airport in Goma. That was seven days ago.

After unloading the C-5A with a forklift, Burgess estimated he had unloaded 300 tons during the previous 30 hours from all sorts of aircraft arriving from different countries.

A tired Burgess said, “I’ve seen the refugee camps. I’ve seen the mass graves. I’ve seen funeral processions like the one we just saw. We need more help here.

“The bodies stacked like cord wood. … It really gets to you.”

Two children ham it up for journalists from the United States. Journalists were told that the rock mounds on which the children were playing and in the background were burial mounds. Photo by Keith Michaud

A funeral procession moves near where a C-5 Galaxy transport is being unloaded of water purification equipment at the airstip in Goma, Zaire, during the summer of 1994. Photo by Keith Michaud

August 2, 1994

Grim images of refugees haunt helpers

(Today’s edition of The Reporter features the efforts of staff writer Keith Michaud and photographer Joel Rosenbaum. The pair accompanied Travis (Air Force Base) crews on a mission of mercy as they delivered water purification equipment to a Rwandan refugee camp in Goma, Zaire. – Editor)

By Keith Michaud

Staff Writer

The images of Goma, Zaire, go beyond frightening. The go beyond haunting.

On a hill overlooking the airstrip, two small bodies lay side-by-side, their faces and most of their thin bodies covered with a cloth.

A small child – perhaps 5 years old – sat on one of the nearby rock piles in a makeshift graveyard with graves of all sizes, from adult to small child.

As the first of the U.S. Air Force transports finished unloading water purification equipment a week ago for thousands of Rwandans dying from cholera and other diseases, a funeral procession came from behind a dirt berm nearly concealing shanty huts.

The procession, complete with 100 or more singing mourners, made its way around one end of the runway where the C-5A Galaxy jet from Travis Air Base in Fairfield was being unloaded. It then moved into a grove of nearby palm trees.

Despite the muggy haze, Mount Kilimanjaro could be seen from miles away, a backdrop to the airport, the camps and the horror.

Relief workers said bodies of more dead were along the road just outside the airport gate, the same road used by refugees to travel from the camps to Lake Kivu, which is contaminated by dead bodies and human waste.

These, by far, are not the worst scenes from the tragedy that has come from a Rwandan civil war that has already killed hundreds of thousands and left tens of thousands dying in refugee camps.

But each image of death, each image of suffering, each image of the atrocities in Rwanda and surrounding countries adds to a pile of horrific woes stacked far higher than stones piled on top of the graves.

Air Force Capt. David Burgess arrived in Goma, Zaire, five days before the Travis jet.

Flying humanitarian aid to Nairobi, Kenya, Burgess volunteered to fly to the tiny airstrip to assess the airport for the expected flights bring aid to the ravaged countries.

I’ve seen the refugee camps. I’ve seen the mass graves. I’ve seen funeral processions like the one we just saw. We need more help here,” said Burgess, weary from nearly single-handedly unloading transport aircraft early last week with a lone forklift.

Other transports, he said, were unloaded by hand.

“The bodies stacked like cordwood. … It really gets to you,” he added.

Hundreds of refugees gathered around the Travis jet, making it difficult for Burgess to unload. The onlookers, mostly small boys and men, crowded in on the jet, its Air Force reserve crew and media representatives accompanying the humanitarian mission.

The men, speaking broken English and passable French, asked for help, any help. The mostly begged for money.

The children also begged for money, but some were happy just to have their photograph taken. Some children wearing little more than rags walked arm-in-arm, apparently with no surviving adults to supervise them.

It is estimated that some 2 million Rwandans left their homes and their crops to flee to Zaire, and hundreds of thousands of others fled to Tanzania, Burundi and Uganda.

By the end of the week, many refugees began returning to their homes despite the continued threat of violence there. Relief workers were trying to set up food stations along the road back to Rwanda to encourage refugees to return home and away from the deadly camps.

The suffering prompted a U.S.-led rescue effort on a massive scale. The U.S. military called upon reserves – its “weekend warriors” – for a peaceful mission.

The C-5A Galaxy carrying water purification equipment from a Redwood City company, Portable Water Supply System, was flown nearly 24 hours straight from Travis Air Force Base to the airport in Goma, Zaire. The flight, because of its length, required twice the normal crew from the 349th Air Mobility Wing and three mid-air refuelings.

Now flights are taking off from military bases in Europe on their way to Africa.

One of the pilots, Lt. Col. John Jackson of Benicia, has been in the reserves at Travis the past 15 years, with 10 years active duty before that. Jackson has flown scores of humanitarian and emergency missions, but delivering the water purification equipment had a special meaning.

“You couldn’t get much more humanitarian than that,” said Jackson. “We want to help provide a safe water supply.”

Portable Water Supply System was up and running within 24 hours, helping provide hundreds of thousands of gallons of drinking water. With more equipment expected, the water was but a fraction of what was needed and relief workers were unable to get much of the water to the refugees because of leaky tankers.

“It’s much more satisfying to do these types of missions,” said Jackson, who is a Hawaiian Airlines pilot away from the reserves. “It’s nicer to try to save somebody than it is to go to war with somebody.”

Jackson’s co-pilot, 1st Lt. Greg Chrisman of Burlingame said, “From a personal level, it’s pretty easy to read a newspaper or watch TV and see what’s happening. … I don’t even think we can imagine the severity of the situation.

“When they called and said they needed people, that was part of my commitment (to the Reserves). I wanted to go,” said Chrisman, who flies for Southwest Airlines.

Jackson and Chrisman over the years have flown missions to Desert Storm and Somalia, and have helped relief efforts after hurricanes and other natural disasters.

Tech. Sgt. Alice Munoz, of Vacaville, has more than 14 years in active and reserve duty. A correctional officer at California State Prison, Solano in Vacaville, Munoz is a flight engineer.

Except for the flight surgeon, she was the only woman on the reserve crew flying the equipment to Goma.

“I’m very patriotic,” said Munoz, “so whatever the Air Force has for me, I’m willing to help out.

I treat all missions the same way because you never know what’s going to happen.”

Munoz was not the only crew member from Vacaville. Lt. Col. Phillip P. Blackburn, Mast Sgt. Wendell K. Asato, and Staff Sgt. Roderick J. Rodda, all of Vacaville, were also on the crew, with Staff Sgt. Robert T. Selmer of Fairfield.

The crew members mentioned that their employers willingly allowed them to take off time for the mission, mostly because of the images shown over the past weeks.

“I think they were more excited about it than I was,” Munoz said of her supervisors at the prison. “I think they know what’s going on over (in Rwanda and Zaire).”

[The following is a column I was allowed to write at The Reporter after I returned. I believe it was published on or about the same time as the story immediately above, but I cannot find the date on the clipping I have of the column. This column was written prior to being given a regular weekly column at The Reporter. – KM]

Children from nearby makeshift villages play on and near burial mounds as a C-5 Galaxy transport is unloaded of water purification equipment at the airstrip in Goma, Zaire, during the summer of 1994. Photo by Keith Michaud

Unshakeable images

By Keith Michaud

Staff Writer

It’s hard to shake the things you see in Goma, Zaire.

A week back from the trip with an Air Force Reserve flight to a tiny airstrip to deliver water purification equipment, I still don’t sleep as well, eat as well or think as well as I did before visiting that place.

Maybe it’s jet lag. Maybe it’s the malaria pills I must take for another couple of weeks. Maybe it’s just what I saw there.

Even though it was just an African airport and not the disease plagued refugee camps, it changed my perspective on the world and what’s important.

We Americans are quick – too quick – to complain about the very little of things. We complain if we don’t have clean underwear. We complain if a flight home is not on time. We complain about being a couple bucks sort.

What do Rwandan refugees have to complain about?

They have life and death. Lately, they’ve had mostly death.

When all the bodies are totaled, there could be 750,000 to 1 million dead between the civil war in Rwanda and the disease in refugee camps in neighboring countries. Many of those camps are around Goma.

There’s a surreal quality to the Goma airstrip. As the C-5A Galaxy from Travis Air Force Base came in low for the landing, young children scurried out of the jet’s path, many knocked over by the wash. It’s a little game they play in Goma.

A fence of rolled barbed wire goes around a least part of the airfield. But there are large holes in the fence and it’s fairly easy for refugees camped not far away to make it to the end of the runway to see the big jet as it is being unloaded.

Americans complain about being overweight and being unable to stick to diets. There were no overweight people at the Goma airstrip. There were a few bloated stomachs, though.

The airstrip there is in a bit of a basin with patches of green and lush hills nearby. Mount Kilimanjaro from miles away peers down through the thick, hazy African sky.

Just beyond the rolled barbed wire were two thin bodies, barely covered with a cloth. Refugees from nearby shanty camps walked by with bundles heaped high on their heads; most barely looked at the bodies. To them, the bodies were just two more of so many.

And just beyond were more signs of death in Goma: stones piled up for graves of all sizes. Children play among the piled stones.

As the crew finished unloading the huge jet, a funeral procession went by. More death.

It’s not difficult to imagine the bodies. U.S. and French military officers talked about the road just outside the airport. Men hardened by training, expectations and experience, they still become choked up when they talked about bodies stacked like cordwood.

But among the images of death, there are still those glimmers of hope. The water purification equipment was up and running within 24 hours. It was enough to give only a small portion of the refugees clean water, but it was a start.

Two children walk down the runway at the airport in Goma, Zaire, during the summer of 1994. Photo by Keith Michaud

And children still play in Africa. They still walk arm-in-arm. They still mug it up for a camera. Children die in the refugee camps, but children are children and they play until they are too ill to play.

It’s not the Africa I saw as a kid in Tarzan movies. It’s an Africa that likely will continue tearing itself apart with tribal wars – wars that will continue to leave hundreds of thousands of people vulnerable.

News stories compared the death and living conditions to hell and the first days of the Apocalypse. That seems close to the truth.

The author was a staff writer for The Reporter when this column was published.